In Watermarks in Scripophily – part 1 I introduced you into the world of watermarks specifically on bonds and shares. This time we’ll talk about watermarks created by the paper makers themselves, perhaps the most obvious category of watermarks in scripophily.

The first watermarks appeared in Italy during the 13th century. They were used to identify the papermaker or the trade guild that manufactured the paper. An interesting question is whether watermarks were invented, or just a side effect in the production process?

images 1a and 1b: When viewed against a light source, this Nira Valley Sugar Co share reveals a watermark pattern of bold vertical and faint horizontal lines. This is an example of laid paper. A detail of the pattern is shown here below. Click images to enlarge. The actual company and its share was described and illustrated in part 1 of this series, see here.

European paper was initially made by dipping a wooden-framed screen, a lattice of metal wires, into a tub of warm water and cellulose fibers, scooping up this pulp, and then letting the water drain out. The cellulose came from cotton linters or recycled cloth (rag), and only much later wood fibers were used too.

The cellulose fibers subsequently matted into a thin layer against the screen. For hundreds of years these screens had a rectangular design with widely-spaced vertical “chain” wires and closely-spaced horizontal “laid” wires tied on top of the chain wires.

In the process the wires in the screen compress the pulp fibres and reduce their thickness. The resulting patterned portion of the paper is thinner and lets more light through than the surrounding paper.

The laid wires yield faint lines in the watermark. Chain wires have a greater impact and are responsible for the bolder lines. This type of paper is known as laid paper. A nice example can be seen above in images 1a and 1b.

images 2a and 2b: The Swedish immigrant Willgodt T. Odhner invented the Arithmometer, a pinwheel calculator. Following the Russian revolution, his company moved from St. Petersburg to Göteborg, Sweden. This 1918 share’s watermark reveals a coat of arms of the paper manufacturer Lessebo, a crowned beehive with the date 1719. The words ‘Handgjord Post’ translate as ‘handmade post’. Image courtesy Wilhelm Leiter

Paper makers found out that they could add special designs to the watermark by sewing wire designs to the screen frame. A paper maker could now incorporate its coat of arms, a logo, or its name into the watermark. The product could now be identified and became difficult to counterfeit. An interesting example is the Original-Odhner share, see images 2a and 2b.

Often paper makers have a remarkable history. The Original-Odhner’s share’s paper manufacturer is Lessebo Paper. The paper mill was originally an iron mill established in the 17th century. In the 1690s the mill started making heavy paper for paper cartridges used for containing a bullet and gunpowder. In 1719 the mill gained permission to manufacture paper, a date that you see in the company’s coat of arms (image 2a). Lessebo Paper still manufactures hand-made paper today.

Over time, the production of watermarks became mechanized. During manufacture paper pulp is passed through rolls with a raised design. The designs applied on the rolls cause density variations in the produced paper. In turn, these density variations make an image or a pattern appear in the paper in the form of various shades of lightness and darkness. We speak of multi-tonal watermarks.

A relevant example can be seen in part 1, see there, namely the Indian Post Office 5-Year Cash Certificate. That paper shows light, dark and even multi-tonal watermarks giving the viewer an impression of depth. Another fine example can be seen on a Olivetti bond, see images 3a and 3b.

Images 3a and 3b: Ing. C. Olivetti & C. was founded in 1908 as a typewriter manufacturer and evolved into computers and smartphones. This certificate, issued 1948, has a watermark pattern, a repeating design that is applied all over the surface of the paper. Watermark patterns can be seen on many Russian railway bonds. In most cases it is not possible to detect whether patterns like these were designed by the paper manufacturer, or by commission of the certificate’s printer or issuer. The pattern on this Olivetti bond consists of diagonally placed geometrical figures. The multi-tonal shade gives you an impression of depth and the pattern appears as a structure of ‘buttons’, looking like bubble wrap plastic, something I usually cannot resist popping!

In the 1700s James Whatman started a paper making business in Maidstone, Kent. He experimented with the wire screen used in the process. Whatman replaced the lattice of laid and chain wires with a screen of a much finer woven mesh of wires. As a result, the paper was formed on a much more uniform surface and showed no watermark pattern of lines, unless a wire design had been sewn to the screen. This type of handmade paper is called wove paper, and its invention led to what we know as modern paper today.

Whatman was probably the first paper company that added a year to its watermark, see image 4b. You may discover on your certificates watermarks by other paper makers incorporating a year as well. The shares in the United Commercial Bank, Calcutta, issued in the 1960s, show the T H Saunders (or parts of it) name with the year 1946. That company was founded by Thomas Harry Saunders. Famous for its diversity in watermark designs used on stamps, bills of exchange, securities, and the like, Saunders won medals at international exhibitions for his light and shade watermarks that were used to prevent frauds.

Images. 4a and 4b: Established in the 1840s as the Auckland Hotel, Kolkata’s Great Eastern Hotel, today known as the LaLiT Great Eastern, hosted many notable persons like Nikita Khrushchev, Elizabeth II, Dave Brubeck and M K Gandhi. This 1937 share was printed on wove paper. Its watermark shows the WHATMAN name, ‘HAND MADE’ and the year ‘1916’.

You cannot interpret a year in a watermark as the year of paper production or as a print date. It should be seen as “paper produced not earlier than” because mills did not always update their watermarks.

Besides their name and coat of arms, paper mills sometimes added to the watermark an indication of the paper brand and the paper quality. That made it easy for stationery businesses and printers to look up the right type of paper in their inventory. As an example, I show here an American paper, see images 5a and 5b.

Images 5a and 5b: The Q1 Corporation was a pioneering microcomputer company. In 1972 they delivered the world’s first personal computer based on an 8-bit general purpose microprocessor, the Intel 8008. The share bears the watermark of the Strathmore Paper Co, founded in 1892, West Springfield, Massachusetts. The watermark shows the brand ‘Strathmore Script’ and its quality ‘100% Cotton Fibre’. Cotton fibres are strong yet soft and create a uniform paper surface that is strong and flexible. 100% cotton paper is often used for banknotes.

In some cases, paper makers add to their watermark the location where the paper was made. Some examples from Indian shares: The Rajnagar Spg. Wvg. & Manufacturing Co Ltd, preference share, 1945, was ‘MADE IN ENGLAND’ and a 100 Rupees share in The Birla Mills Ltd, 1920, reveals ‘MADE IN CANADA’.

More of a surprise is a 100 Rs share from The Gold Mohur Mills Ltd, 1926, Bombay, telling us ‘MADE IN AUSTRIA’. Another example that illustrates the export of quality paper products is shown in images 6a and 6b.

Images 6a and 6b: From Egypt, the shares from the Alexandria Pressing Company that were issued in the 1950s have a watermark showing the name of the Norwegian company ‘BORREGAARD’, the paper type ‘TUB SIZED LEDGER’ and the location of the paper mill ‘MADE IN NORWAY’.

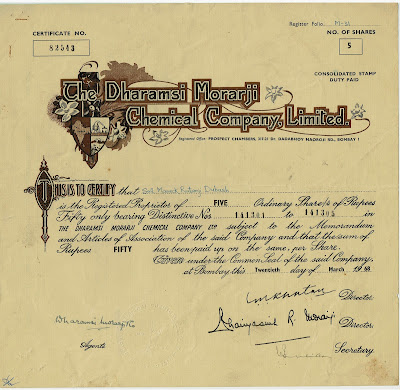

I conclude this part in the series with one of my favorites: a share in The Dahramsi Morarji Chemical Co Ltd, Bombay (DMCC). Its watermark shows the line LUCKY PARCHMENT, a design of a jockey racing a horse, and the words RAG CONTAINING underneath. See images 7a and 7b below.

Parchment paper is not to be confused with “parchment”. The latter is a writing material made from animal skin. The former is a type of cellulose-based paper (made from wood pulp and cotton fibers) which has been treated chemically to make the paper stronger, more heat resistant and above all non-sticky.

You’ll find the words PARCHMENT also in the watermarks of shares from McLeod and Co, Ltd (1940s) and many other scripophily examples. In my example, LUCKY PARCHMENT is a parchment paper brand from the Indian paper company Ballarpur Paper and Straw Board Mills, Ltd.

RAG CONTAINING is another line of text in the DMCC watermark. Rag paper or cotton paper is primarily made of cotton linters or from used cloth (rags). Cotton paper may last many decades without any sign of deterioration, see also images 5a and 5b before.

Images 7a and 7b: This share in The Dahramsi Morarji Chemical Co Ltd was issued in 1968. The company's headquarters were located at Dr Dababhoy Naoroji Road in Mumbai. The certificate shows the coat of arms of the company, including a tiny map of India, and has a watermark of a racing jockey.

The DMCC’s remarkable jockey watermark seems unrelated but it is not. I learned from scripophily expert Sayeed Cassim (see also here) that the Ballarpur paper company was founded by Karam Chand Thapar, who headed the Thapar Group of companies. The Thapar family was involved in race horse ownership, hence the jockey.

Time for a quick review. The first watermarks were formed, likely unexpectedly, in the production process of what we now call laid paper. Paper makers then added a logo, their coat of arms, or their name to the watermark design. Some of them further added a year, a paper type or brand, and also a location where the paper was made. If you haven’t done so already, you might start viewing your certificates against a window.

In part 3, I’ll show that paper manufacturers start adding watermark elements on behalf of one of their important customer segments: security printers.

F.L.

This article was initially published in Scripophily magazine No. 114, December 2020.

You might be interested to read : Watermarks in Scripophily - part 1 Introduction

No comments:

Post a Comment